Energy Performance of Buildings Directive – Taking the next step towards zero energy buildings

As EU trialogue discussions on the latest revisions to the EPBD complete their final phase, AUDREY NUGENT, Director of Global Advocacy, World Green Building Council, speaks with Robbie Cousins about what fundamental changes and timelines can expected.

Climate change, removing fossil fuels and achieving energy independence, not to mention the soaring price of heating and energy poverty, are all issues for which building policies can provide solutions. Individual EU governments are fully aware of the need to decarbonise our buildings and the need, now more than ever, to protect millions of people living in leaky and wasteful buildings against soaring energy bills.

To this end, Europe’s architects, engineers and construction sectors need a clear zero-emission building (ZEB) standard to align the design and construction of future builds with the goal of climate neutrality.

Energy Performance of Buildings Directive

The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) has been the cornerstone of EU regulation on sustainable building, leading to the introduction of building energy rating (BER) and nearly zero-energy building (NZEB) standards in Ireland. Currently, negotiations at EU level on revisions to the EPBD are nearing completion.

Fundamental changes anticipated as part of the revisions under discussion include:

- The introduction of mandatory whole-life carbon measurement requirements

- A transition from nearly zero-emission buildings to net zero buildings

- The introduction of minimum energy performance standards, and

- The introduction of building renovation passports or roadmaps.

Trialogue discussions between the three EU bodies – Commission, Parliament and Council – on the revisions have now entered the final phase. The trialogue process begins with the Commission putting forward its proposals. The Council and Parliament then review these and put forward their position.

Local politics has, as always, meant that everyone involved in the negotiations has been walking a political tightrope, and they all know that time is running out as far as the climate catastrophe and global heating are concerned. It should also be noted that once agreements have been reached at an EU level, the legislation must still be transposed at an individual member-state level. So, the clock is ticking.

As director of global advocacy with the World Green Building Council (WorldGBC), Audrey Nugent leads WorldGBC’s advocacy and policy work, and she also collaborates with Green Building Councils around the world to champion public policies that drive the systemic change needed in the built environment.

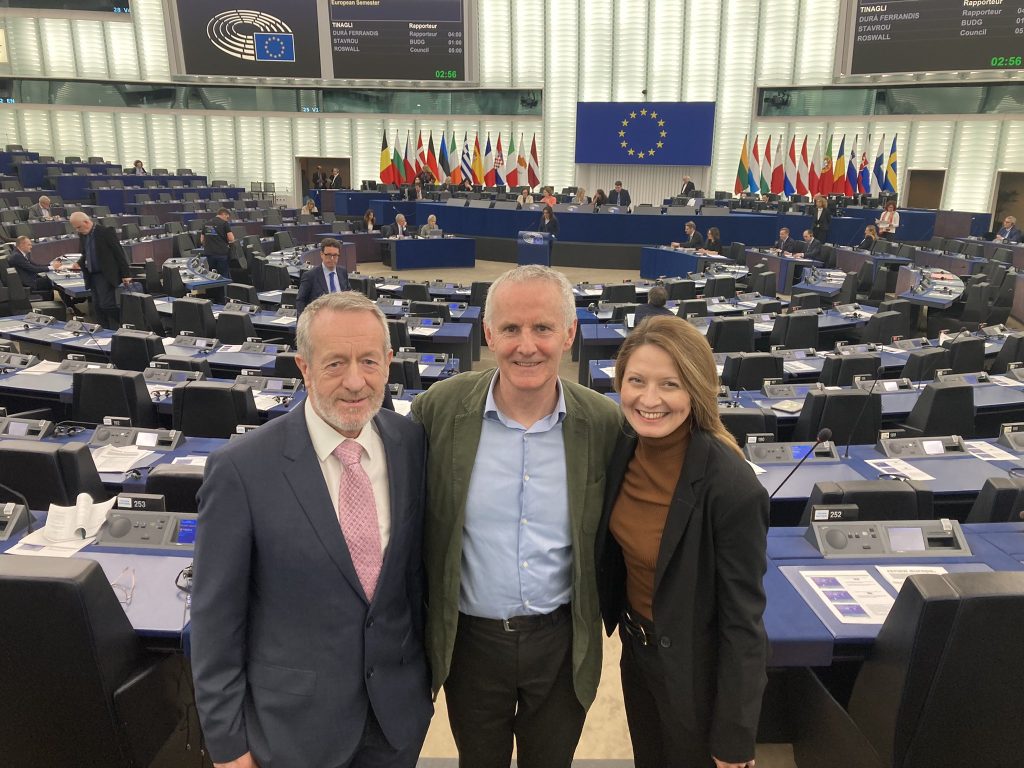

In Europe, amongst others, she works with representatives from the EU Commission to ensure that the EU adopts legislation that delivers a decarbonised, circular and well-designed built environment. She is passionate about delivering a holistic and integrated approach to reduce the carbon impact of the built environment, and she has been working closely with MEPs, including Ireland’s Ciaran Cuffe and Sean Kelly, to revise environmental policy at an EU level.

She explains that from a WorldGBC’s perspective, the priorities for revising the EPBD are:

- Minimum energy performance standard (MEPSs) – Support the introduction of an MEPS that can drive a ‘Renovation Wave’, which should be introduced promptly on a pathway to full decarbonisation by 2050.

- Energy performance certificates (EPCs) – These should be harmonised, with performance classes rescaled with the aim of a zero-emission building stock by 2050. EPCs should also include whole-life carbon metrics.

- Zero emission buildings (ZEBs) – The WorldGBC supports the introduction of a ZEB definition as a much-needed upgrade to NZEB. The definition should be upgraded by 2030 to take into account embodied and operational carbon.

- Whole-life carbon reporting – Whole-life carbon (WLC) reporting should be introduced for all new buildings by 2026 to allow the establishment of whole-life-carbon benchmarks and limits this decade.

Revisions to the EPBD

Audrey Nugent comments that the revisions to the EPBD could lead to the harmonisation of EPCs, establish a new standard zero-emission building definition, and introduce building renovation passports (BRPs) and WLC reporting.

“All of these things will substantially impact the Irish construction industry and result in further changes to minimum energy performance standards for buildings. But there are different perspectives amongst EU policymakers on the timelines for changes to be introduced, as well as some critical criteria also to be agreed, and a number of significant compromises will have to be made to get the changes over the line.”

She adds, “This will have implications for new builds and the renovation of existing buildings to get them to a certain level before they can be sold or rented. To date, the focus has been very much on new builds, but the revisions will bring what can be done about making existing building stock more energy efficient into focus. The EU trialogues around this have been tricky, particularly concerning what the MEPS framework will look like.

Minimum energy performance standards

In March of this year, the EU Parliament adopted measures to improve the energy efficiency of buildings across the EU. The proposals aim to ensure that all new buildings produce zero emissions from 2028 onwards and ensure minimum energy ratings for existing residential buildings from 2030.

As a first step in the trialogue, the EU Commission proposed that existing public and other non-residential buildings must have at least an EPC of class F by 2027 and class E by 2030. It further proposed that all existing residential buildings must have at least an EPC of class F by 2030 and class E by 2033. The Parliament responded by proposing a more ambitious timeline. Among the changes proposed by Parliament is that the energy rating of existing residential buildings will have to meet a minimum class E rating by 2030 and gradually improve from there onwards.

Audrey Nugent explains that the Parliament proposed public-owned and non-residential buildings should achieve at least an EPC class E by the start of 2027 and at least class D by the beginning of 2030. However, the Parliament’s goal of achieving these ratings for residential buildings may be a point where compromise will have to be found.

“The WorldGBC supports the introduction of MEPS, but the ambition of EPC classes and dates should be strengthened if the Commission wishes to deliver on the goal of creating a Renovation Wave.

“Under the proposed Commission revisions, we see the goal of residential buildings achieving class E after 2033 as disappointingly unambitious, especially given the European Commission’s drive to tackle energy poverty. We would also like to see the Commission commit to assessing the feasibility of adding WLC metrics to MEPS.”

The Renovation Wave to which Nugent refers is the EU’s dual ambition of energy gains and economic growth. In 2020, the EU Commission published the strategy ‘A Renovation Wave for Europe – Greening our buildings, creating jobs, improving lives’ to boost renovation in the EU.

She adds, “An improved EPC framework would help move our building stock towards being climate neutral. Measures would include calculating how you could reduce the WLC emissions of a building, the expected energy savings and health and comfort benefits.

“This could also be part of a digital building logbook, which could be built up into a repository of information that could, in turn, be used for national climate action plan revisions.

Whole-life carbon

Speaking about the anticipated introduction of mandatory WLC calculations, Audrey Nugent explains the WorldGBC’s perspective, “The reason we call for WLC calculations to be considered at the building level is so one lower embodied carbon product is not necessarily being prioritised over another if it is not right for the particular design. When considering WLC, you should not be making a decision on specific products; you are assessing how the building is designed, how much material it actually uses, the types of materials that are used and what works best together, as well as how they contribute to the building’s operation and how they are treated once, if it is the case, the building is deconstructed.

“It’s an overall assessment of how the building performs over a life span of 50 years. So, you are not at the outset saying you need to be using one particular building material; you are looking at what type of building it is and carrying out a WLC assessment of how it will be used and what it will look like.

“This doesn’t mean there will be a huge shift in the types of products being used immediately. The idea is to activate thinking about the whole life of the building and the design and construction considerations that should go into it.

“For now, it might mean looking at the size of the buildings, for instance, the square footage, what type of material is most efficient for the building when it is designed, and how it is foreseen to be used.

“We are already seeing more innovative use of materials emerging as a requirement as people start to carry out WLC assessments. Practitioners are learning from the jigsaw of what works to get an overall lower WLC value.

“Within the context of the EPBD and what is being proposed for the mandatory WLC reporting requirement for all new buildings, the Commission has put forward 2030 as the year for this to be in place, and 2027 for all new buildings above a certain floor area. But, again, the Parliament has a more ambitious timeline of the reporting requirement for all new buildings to be in place in place by 2027. The Parliament goes one step further, and its position would require member states to set WLC targets for all new buildings from 2030 onwards, which will inevitably be one of the topics related to WLC under discussion during trialogue discussions.”

Some EU states have made advances in WLC reporting, with Finland, the Netherlands, and France front runners, and Denmark has just introduced its own WLC legislation.

From an Irish perspective, EU parliamentarians Ciaran Cuffe and Sean Kelly, as rapporteur and co-rapporteur on the Industry, Research & Energy (ITRE) Committee, are responsible for the revision of the EPBD. So there’s a sense of leadership from Irish politicians on this, and they have not been found lagging.”

Renovation passports

The requirement for renovation has always been a tough nut to crack. It is complex, and there are multiple challenges, whether policy implementation, financing, awareness raising, and the upfront costs and, of course, returns on investment.

With this in mind, the key challenge is to get a pan-EU renovation wave off the ground.

Audrey Nugent comments, “While Ireland’s renovation rate is still very low, at EU level, some of the mechanisms Ireland has in place, such as its community models and one-stop-shop concepts, are seen as having good potential to scale.

“The Commission has proposed that BRPs should set out a roadmap for all buildings to be ZEB standard by 2050. This would cover criteria such as what the benefits look like in terms of energy savings and greenhouse gas emission reductions. It would also include a list of indicators such as WLC measurements, indoor air quality and other forms of relevant data.”

The Commission has proposed an ambitious timeline for member states to introduce BRPs by 2024.

“From the work we have done on national renovation strategies, and within this context what we have learned that to be effective, the EU bodies need to bring together a diverse community of stakeholders to make this work because it will not work if governments try to run these alone as has been the case in the past.

“The Council is looking to push out the deadline for BRP introduction to the end of 2025, with the passports voluntary at that time. Again, we have to see what happens in the final trialogue.”

The WorldGBC has made a series of recommendations within its WLC roadmap on what a BRP should look like and what would need to be in it. The Irish Green Building Council has carried out a lot of work developing what a model BRP could look like.

“We have proposed that there should be an individual climate action roadmap for each building that would incorporate a BRP, and that it’s not just for existing buildings, but future buildings as well. An outline within the roadmap would set out how progressively tightening minimum energy performance standards for that building would reduce WLC emissions and set out expected energy savings and health and comfort benefits.

“By making the passport digital, as part of an overall digital building log book, this would act as a repository of all material and information related to the building, which, in turn, could be linked to national climate action plans. So, there’s a link between individual buildings and national climate action plans that member states are working on.

Minimum Energy Performance Standard introduction

With regard to the MEPS, the WorldGBC believes that the EU can’t expect people to comply unless there is a clear trajectory and introduction time and support in terms of what the introduction of MEPSs would mean for various sectors.

Nugent explains, “For individual member states to get to a stage where they are compliant with the MEPS, this would require an acceleration of the rate of renovation across the EU, as most of the EU’s building stock was constructed before the introduction of the EPBD, and the MEPS will be more relevant to older buildings than new builds.

“The Commission has put forward that public-owned and non-residential buildings would need an EPC of class F by 2027 and at least class E by 2030. This means just moving the worst-performing buildings up to what is still a fairly low-performing standard. For residential buildings, the Commission has the less ambitious timeline of Class F by 2030 and Class E by 2033.

“The Parliament, as I have already said, has a more ambitious position; they want a higher class of performance to be achieved by those same dates, so rather than F and E, they want an E and D standard by 2030 and 2033, respectively. Again, we await to see the outcome when the agreements from the trialogue are published.”

Zero Emission Building standards

In terms of the ZEB standard and the definition of what this will be, it is still being thrashed out in the negotiations.

“The timeline for ZEB introduction, which is under negotiation, is that all new buildings will have to meet the ZEB standard by either 2027 or 2030. We hope that because of their familiarity with NZEB, member states and stakeholders would have a better understanding of how to comply with the ZEB standard.”

Fossil fuel phase-out

Fossil fuel phase-out is another critical area under discussion in the current trialogue.

The Commission has put forward that from January 2027, as part of the multi-annual financial framework, no incentives should be given for fossil fuel heating systems. The Council has proposed that this be the case from January 2025, and the Parliament’s position is that it should be January 2024. The Parliament went one step further and put forward a measure that member states should ensure that fossil fuel boilers cannot be installed in new buildings once the EPBD revision comes into effect. However, at the same time, the Parliament introduced a loophole to exclude hybrid boilers from this measure, which means that hybrid boilers which can partly use fossil fuels could be installed.

Audrey Nugent comments, “The EU Commission has put forward a legal basis for the phase-out of fossil fuel boiler bans, but no EU-level phase-out. When the Parliament was going through its vote on fossil fuel phase-out, one of the concessions they had to give to get it through was a loophole that hybrid heating systems or boilers that are also certified to run on renewable fuels might not need to be considered fossil fuel heating systems. There is a concern that this is a significant loophole, and we are watching to see how this evolves.”

In conclusion

Audrey Nugent concludes by saying despite the stumbling blocks, the agreed revisions in the EPBD will move the construction sector closer to being carbon neutral.

“The final trialogue started on 31 August. We’re hopeful that the outcomes from this will be published in Q1 2024. There would then be a period of about 18 months to transpose the agreements into individual states’ legislation. This might mean the revisions will be in place at some point in 2025. And, depending on what’s agreed in the trialogue, if more ambitious people get their way, some of the provisions might be coming down the line in two years. But there’s going to be a fair deal of compromise needed yet to get this over the line.”

She closes by adding it should be noted that the EPBD is just one area of legislation to be addressed.

“There are a lot of other initiatives coming out of the Commission with regard to buildings. There is also a piece of work around better understanding the existing building stock across member states and updates on the Waste Framework Directive as well as new construction products legislation.

“Overall, there is a comprehensive range of improvements coming down the line that construction professionals will want to keep an eye on,” Audrey Nugent concludes.